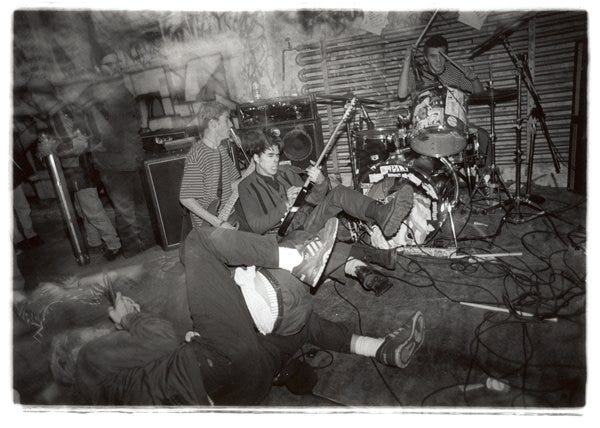

INTERVIEW: TONIE JOY PT II

In this second installment of my interview with Tonie Joy, we discussed the formation of Universal Order of Armageddon, joining Born Against and touring in the 1990s.

Photo: Justine DeMetrick

Moving from Moss Icon to Universal Order of Armageddon, there’s a contrast in sound. With UOA, the songs were shorter and more direct. There also seems to be a more pronounced aggression when compared to Moss Icon. Was that a conscious effort?

It wasn’t conscious and had more to do with the other people in the band. With UOA, my first instinct was to do something like later Moss Icon, but when I started playing with (drummer) Brooks Headley, I found his drumming to be aggressive in a very progressive way. It was the drums that shaped the sound of that band.

Would you say the posthumous interest in Moss Icon began as you were out playing in UOA?

UOA was playing out more than Moss Icon, so I was meeting a lot of people and became an unconscious ambassador for Moss Icon. Another thing is someone in San Diego or Germany just thought of Moss Icon as a band from D.C. They didn’t know the small geographic detail of Annapolis, Maryland being forty-five minutes away from D.C. I think that had something to do with the interest as well.

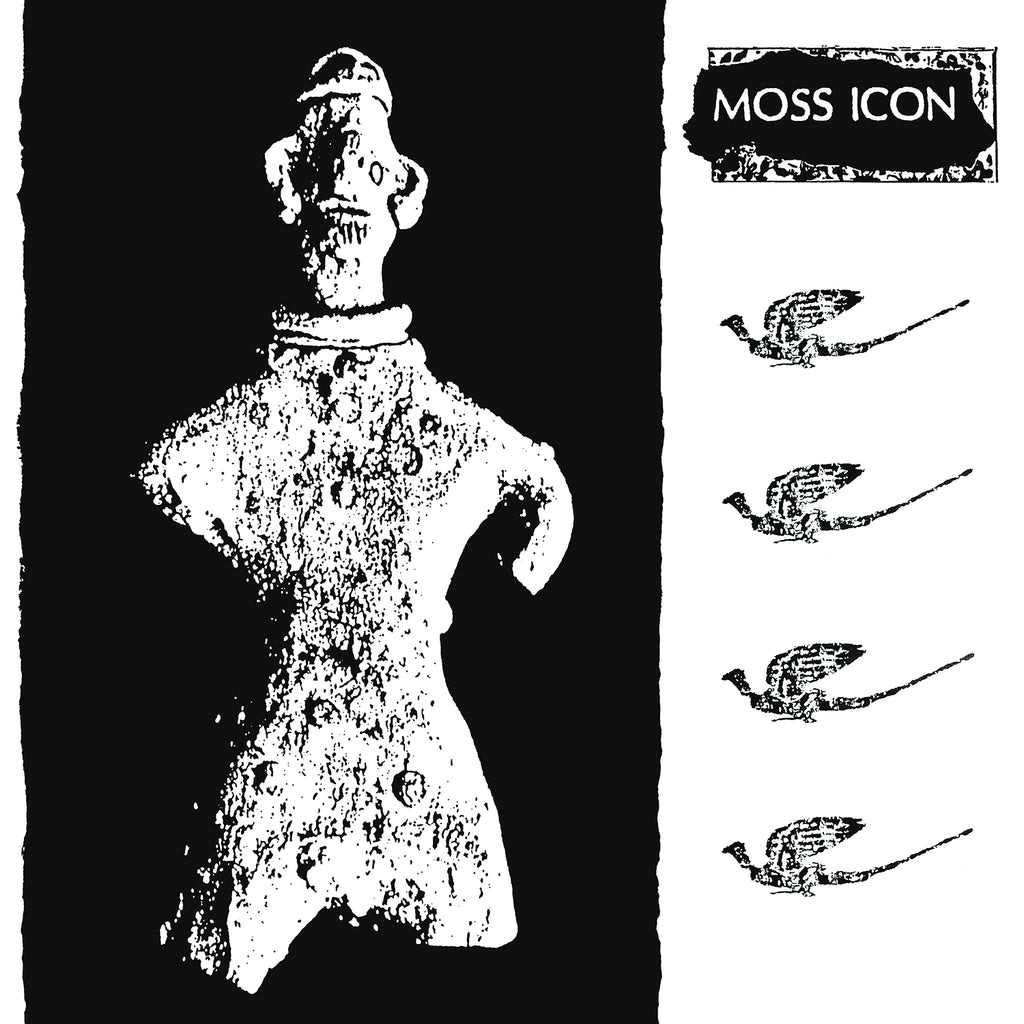

What was the catalyst behind Vermiform releasing Lyburnum Wits End Liberation after Moss Icon broke up?

I always wanted to put that album out but never had the money and then the band broke up. When we played at ABC No Rio with Born Against, we met them and stayed in touch with Sam. I don’t think that show blew anyone away, but I think Sam liked that we were kinda fuckin’ weird. By that point, Brooks and I were playing in UOA, but we also started playing in Born Against. I was around Sam a lot and he asked if he could put out the unreleased Moss Icon record. No one had shown interest in the band and I really dug what he was doing, so I said sure.

What were the difficulties with the album as far as the packaging and sound?

The difficulties can be laid on my own flakiness and young craziness. I liked (the bass player for the band Ignition) Chris Bald’s artwork and talked to him about contributing something to the album. I ended up going to his place in D.C. one day and looked through a bunch of stuff and found a piece that was really cool. I thought the geometric vibe fit the stuff we did on our records. On the first pressing, I thought it looked too washed out. I guess they sold fast because Sam wanted to make more. I tried to fix the problem with the back cover, and it looked cleaned up, but it wasn’t what I wanted, and regretted deviating so much from the first try. I also had an idea for there to be more photos on the back cover but had lost them by the time Sam wanted to do the record. They didn’t turn up until years later when my mother died and I was cleaning out her house. There was also a problem with the front cover that was my own fault and never corrected it. I’m sure it was just real OCD shit that no one else would notice.

Now, thirty years later, Jeremy at Temporary Residence has graciously given me the opportunity to fix all of this. My life has been this whole string of fuck-ups on every level, so when Jeremy showed me what he laid out after explaining everything to him, it was a little bit of redemption. It’s nice to have it remastered, but that happened ten years ago when Jeremy did the complete discography. When I heard the before and after I was blown away. That’s when it really hit me that when you’re young you don’t know much. We never thought to get anything mastered properly or have the vinyl not sound like a flexi-disc that came out of a kids’ coloring book. I had the recordings and knew what it sounded like before it was sent to the pressing plant and somehow they managed to make it sound like shit!

Do you want to talk about being in Born Against?

I loved that band. I remember taking a bus from Annapolis to Baltimore and getting a ride with a bunch of kids I barely knew to see Nausea and Born Against in Philly. After that, I set up a show in Annapolis for them. They approached Brooks to be their drummer just when we started UOA – literally within the same month or two. Then Sam and Adam said they needed a bass player too and since I was already playing with Brooks, it seemed like a no-brainer.

It was interesting to me because I had only been in a few bands up to that point and I liked the idea of just being a hired gun in one. By the time I joined, Sam and Adam had been grinding away hard at the band for a few years, touring and selling records on a grassroots level. Once I began playing with them, I realized they were burnt out and pretty jaded. I’m not sure if that was the case, but that was my perception. So, I think it was bad timing on my part for joining the band at the point they were almost over. I wasn’t too into some of the songs I recorded on. I didn’t really give a shit about a band like Screeching Weasel and never understood doing a split record with them. I guess the guy was nice and would let Sam and Adam stay with him on tour.

There was also a humor element coming in that I didn’t think fit well with the band. To me, Born Againt was a serious, intense band. They presented socio-political ideas in a way that resonated with me because it wasn’t some asshole preaching at you. The humor fit more with what Sam did later in Mens Recovery Project. I will say there are a couple of songs from when I was in the band that are fucking awesome. There are one or two where I contributed to some extent, but it was a great experience. I especially like the songs from before I was in the band. The first ep and Nine Patriotic Songs For Children are still two of the greatest records of all time to me. To sum it up, it was a cool experience.

I feel this time in the American underground that revolved around bands like UOA or Heroin is never really recognized for how experimental it was. But I guess there were bigger things going on during the 90s that captured peoples’ attention.

It was a weird period of time because there was the grunge thing, the larger, indie rock thing, and what we were doing, which was super obscure. When we were on our first tour and got to Washington state, there was interest in UOA from Kill Rock Stars. That was when I started to see all these subgenres in the underground cross paths and I found this very encouraging because I didn’t want to be putting out our records on my own. I wanted someone like Touch & Go or Matador or some label that had its shit together to do it.

There was a lot of idealism at the time, which was cool, but there were people back then that were so pious about DIY shit. These were people who thought making 500 records in a burlap sack with a potato print on it was some pious statement. The record was still pressed on petroleum that came from some fucked up company. Your shirts are printed on cotton, one of the most pesticide-infested crops in the world. If you want some real piousness that’ll work, go buy some land and live off the grid. Grow your own food and get solar panels because that’s the only DIY shit that makes sense. If major labels aren’t telling you how to sound and throwing money at you to be more productive in your art, then that’s fine. There were bands back then that get unjustly overlooked. Maybe it was because they didn’t last long or they didn’t know how to deal with the music business. But maybe they just wanted to be that obscure — who knows? I did love the creative element of the DIY thing but at the same time, I didn’t want to be doing that until I was 70. I had different ideas that I wanted to evolve – or maybe even mutate.

What was it like touring with UOA?

I was doing something I only imagined, so it was great. The first time we came to San Diego, we met all these people who felt more like my peers than anyone back in Maryland and found there were way more people interested in us in other states. But it was so stressful and difficult to do when you had no money. I ended up fixing stuff on the van because we never had money to take it to a shop, and because of that, I ended up working as a mechanic when I got older. With the first tour, I did my best with booking it. It was over five weeks with the last four or five shows falling through. We had a show in North Carolina with Polvo and I canceled it. In hindsight, that was stupid. I must have had almost twenty nervous breakdowns on that tour. By our second tour, we were on Kill Rock Stars and had their support, but I was super jaded and negative by then. That tour killed the band. By the time we got back, we either wanted to kill each other or ourselves. It was a great adventure, but it fucked my mind up. Sleeping on top of the van in the middle of the desert was a priceless, surreal moment – and we didn’t even need to buy drugs!