In observance of the passing of Effigies vocalist John Kezdy this weekend, I am posting this interview I conducted with him in April of 2006. It was initially done for the oral history I did on Midwest Hardcore for the long-gone Swindle magazine but went unused as the piece was whittled down to concentrate solely on Detroit and Touch & Go Records. Enjoy.

Tony Rettman: Although Chicago and Michigan aren't that far away from one another, it seems the early Touch & Go scene and what the Effigies were doing at the time aren’t thought about as a complete entity. Why do you think this is?

John Kezdy: You have to remember, those were pre-Internet days. Communication between scenes was relatively poor. Unless out-of-town bands came in to play there would be very few musical exchanges. Only a few record stores stocked punk. The radio was even bleaker. Except for a few shows on one or two very low-powered stations, there was nothing worth listening to. It was completely possible not to know about good bands just a hundred miles away.

What was the specific time the Effigies started playing out?

We played our first gig on a Sunday night in November of 1980, at Oz, in Chicago. The audience was a small crowd of regulars, and I think we surprised a few people. No one else was doing what we did. I think initially we were perceived as outsiders. This was a scene dominated by poseurs and art students, pure consumers and imitators of the London and New York scenes. Our position in the pecking order changed after we started playing out. We wanted to make music, and we were one of the first punk bands in the city. This is somewhat surprising when you consider that punk had already been around for four years by that time.

If the Effigies are known for anything, it's for going against the grain of the party line politics of early Hardcore. Did you get a lot of flack for this? What was your problem with political bands? Did you just not want to see people be sheep?

An interesting question that probably requires a much longer answer. Hardcore is not synonymous with punk. Hardcore was one of the last stages of what might be defined as the American punk era, loosely from 1977 to 1985. The reason for the name itself is that Hardcore fans were the ones who stuck to the original fast and loud ethos after many original bands and fans had moved on. Hardcore was the diehards of punk at a time when punk was perceived to be passé and played out. Hardcore has stuck it out, though, and now has its own niche. By definition, it's a sub-group and a much narrower type of music than punk.

The Effigies were never really hardcore. In fact, by the time the Hardcore scene had dug in its heels circa 1985, The Effigies weren't punk enough for many people. We were loud, but not always fast, and unlike most thrash bands, we also tried to write songs. I don't think a lot of the bands that came out of the 1979-80 wave were Hardcore. Black Flag, Husker Du, Naked Raygun. Punk, yes. Hardcore, no. I've always considered The Effigies to be a punk band.

The early punk scene in Chicago consisting of Naked Raygun, Strike Under, Big Black, and Da was musically diverse and was composed of people with all manner of politics. Whatever the politics, though, they generally stayed below the surface. It wasn't until much later that I discovered what some of these people's politics were, and to this day I can't figure out some of them.

Blinkered, humorless, and literal-minded, the political types never understood punk. In the early days, they instinctively knew that it was a reaction against the culture of the 60s and hippies in particular. They did understand that much, and it bothered them.

The first punk band I ever saw was The Ramones. They played at a club in Madison called Bunkys in 1978. It was a high-end jazz club, small, clean, and well-wired. Anyway, I got there a little early and noticed some people mingling outside. They weren't going in but seemed to be handing out flyers. "Boycott Fascist Culture" they read. We're talking about The Ramones.

Goobers from INCAR were boycotting the gig, marching in circles outside Bunkys. "Hey ho, fascist culture has to go" - blah, blah, the nursery rhymes. The situation became emblematic. They were utterly clueless about music. The flyer was so ridiculous on its face that we reproduced it and inserted it in the Body Bag singles without comment.

Each one of those singles was hand-packed at one of our record parties. We'd get beers and sit in Steve's basement gluing record sleeves and inserting vinyl and ephemera. The longer we worked, the more carried away we got with the inserts and the graffiti inside the sleeves. Word got back to us later that some people were, uh, offended by the sleeves.

A few years later, every idiot was in a band that had a blueprint for world revolution. Hearing kids bitch about high school and surfers scream about turf never amounted to much, so bands then tried to sound deep by talking politics, and the formula was born. Reagan was the devil in those years, so everything became Reagan this, Reagan that. Loud, fast, and mechanical songs. Hardcore became simply a sub-culture of complaint with a language of simple political-sounding terms that everyone could parrot - A slave morality for kids that knew just enough about trying to sound political. The thing snowballed because by that time anyone who sang political slogans had a ready-made audience, just the same way some Christian bands play up a religious angle these days. By the time the political zealots had injected themselves into the music scene, just about anything that was interesting was taken out of it. Punk was dead by the time Maximum Rock and Roll became its mouthpiece. The Effigies weren't a part of that, I'm happy to say. Our differences were more than musical.

What was your problem with Jello Biafra?

No problem. We have different views of the world, but personally, I like him. He's a character and I don't think many people take him seriously, perhaps least of all himself. In any case, it borders on the ridiculous to push the peace, love, and understanding message for the rest of the world when your own bandmates are suing you. It's a funny thing about these anti-capitalist types, they always end up arguing over money.

What are some of the more memorable shows you played from those days?

On our first tour of the winter 1981-82, we played a lot of big gigs on the West Coast. Once, around the holidays we bounced between LA and San Francisco three nights in a row, playing gigs that included a Paul Rat show at The Factory and some other huge show in L.A.. I liked the Wilson Center Show in D.C., and just about all the shows we did at Club C.O.D. in Chicago.

What was the beef with Articles of Faith? Did you just think they were Johnny-Come-Latelys? Have you spoken to anyone from the band recently?

No one I know has anything against Articles of Faith. We never really had much contact with anyone in that band. Their former drummer is now a street musician and I see him playing at the intersection of State & Randolph Streets in Chicago occasionally. It's his corner. That's the only contact.

It's true, they were latecomers. They called themselves Direct Drive and played Springsteen covers until Bondi went to D.C., saw a punk gig, shaved his head, came back to Chicago with the zeal of a convert, and changed the name of the band. They picked up a lot of fans among the younger kids, but it wasn't really our scene.

In the few interviews I've done in the past couple of years, I was asked about Articles of Faith a couple of times. The questions were always phrased a certain way. I began to wonder why anyone bothered to ask me about them since we really didn't have much to do with them when they were around, and in my circles, they almost never come up in conversation these days. About ten years we did get into one of those where-are-the-now conversations and someone said Bondi was in Seattle working for Microsoft - going full circle on the corporate thing as it were, from Boss to DOS. But that's it. We had nothing to do with them.

I mentioned this to the guys doing one of the last interviews, and they kind of laughed and told me that I should read some notes Bondi had posted on the Internet. He sure has a lot to say about the Effigies, they said. O.k. I found the notes and passed them along to some other people. We all had a laugh. Later, someone sent me even more stuff he'd written. It was then that I figured out why this issue kept coming up. Bondi had created a unilateral controversy between The Effigies and AOF for a reason that's only known to him. It's clear that he's upset, but I don't know why. He gets facts wrong and spills a lot of bile in his screeds, but I don't know where it all comes from. They told me that his rants were over the top, but in one paragraph he libels me by association then casts himself in his own movie by recounting how he jumped out of a crowd to punch out a junior Mussolini at some kind of tent meeting he attended. And at that point, any reader is surely asking himself what any of that has to do with anything. I suppose it would be funny if it weren't so bizarre and unhinged.

Jourgenson got upset about us too, for some reason. It became important for him to tell people he was not like us. Hence, "Effigy" on the first Ministry album.

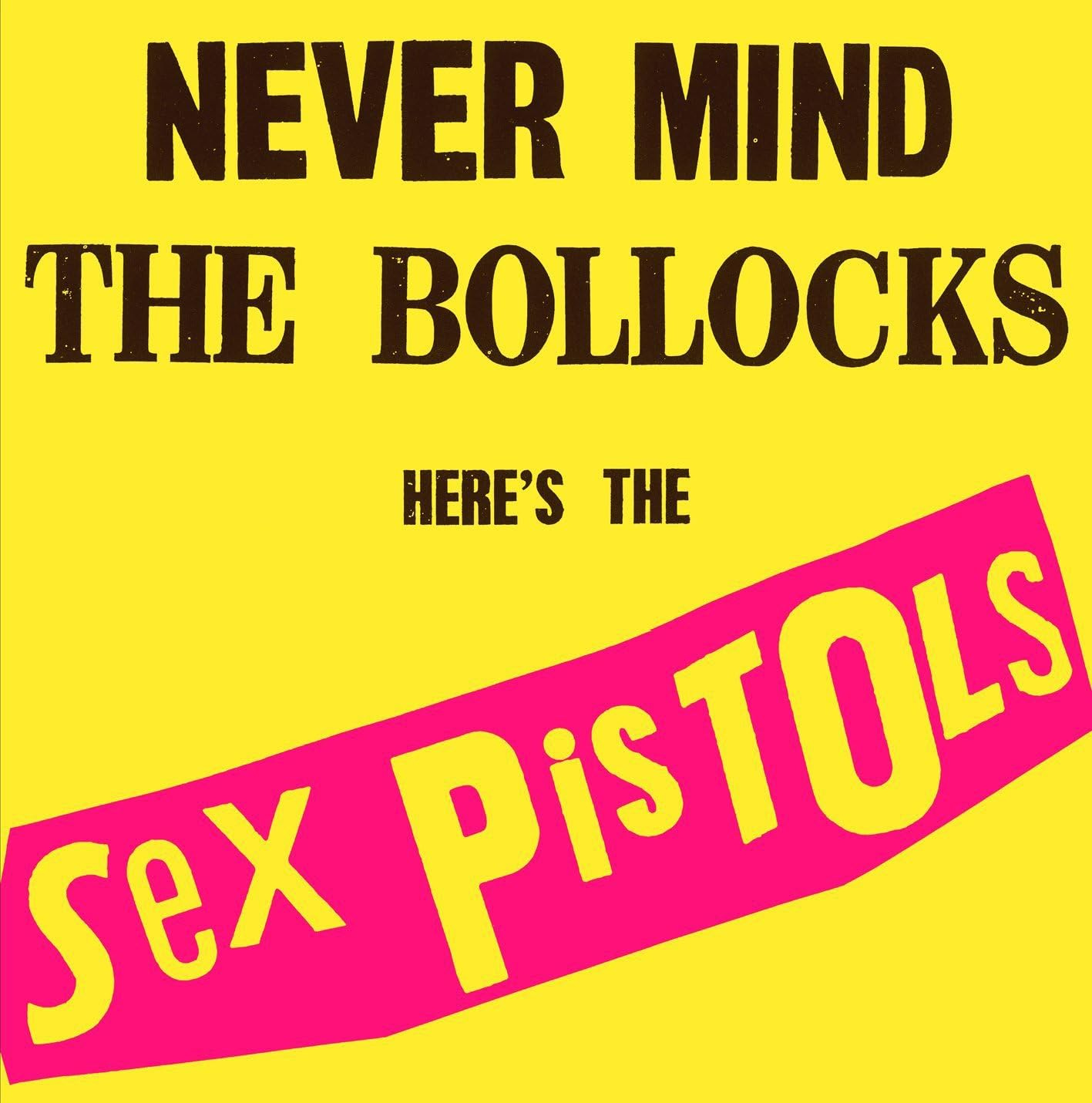

Give a brief description of how and where you grew up. Do you think the environment you grew up in was one of the factors that got you interested in Punk? Steve and I grew up in Evanston. Paul grew up in Morton Grove but later moved to Chicago. Rob McNaughton has lived in Chicago all his life. Earl, our first guitarist, moved to Chicago from upstate New York. We were in high school when we first heard of punk. The papers had lurid blurbs about the stuff going on in London, but the music industry was in one of its slumps and I thought it was all a gimmick to break new music. It wasn't until I heard Never Mind the Bollocks that the whole idea dawned on me. I was in Madison at the time, and the local progressive station featured the album on their album hour. The old hippies were afraid of it. They felt compelled to play it, but they edited the record, cut some tunes outright ("Bodies"), and gave a long disclaimer before it went on. I taped it using a timer, so I didn't listen to it that night. I had some other stuff on the tape that I would always rewind to, and sometimes I overshot the counter on my deck, leaving me to start the play button somewhere in the middle of Bollocks. Once I heard "Pretty Vacant" I got it. The bulb went off. It was the music I had been waiting for

.I had been listening to Hard Rock for much of my teenage years. I listened to top-40 radio as early as 1966. Chicago had two stations with identical formats that competed mainly with the personalities of their DJs. I got an old beat-up tube radio that someone was going to pitch. I listened to the radio for hours at a time.

The harder stuff I listened to in my teenage years never seemed to do it for me. If it was hard, it was also stupid; if it had ideas, it was usually soft and/or pretentious. My high school years are a story of youthful alienation. A couple of guys affiliated with the band went to Evanston Township, a huge school full of all kinds of people, yet we fit in with none of the existing groups. Never wanted to. We weren't even a group unto ourselves, just a few guys who disliked the school and its whole social scene. Jocks, dopers, junior professionals, actors, intellectuals. Couldn't stand any of them. Even rockers had this whiff of dorkishness.

It wouldn't be right exactly to call those years formative, though they led right into punk for me. Anyway, at some point one ought to grow up and realize that the things that mattered in high school aren't important. My disaffection had other sources and went much deeper.

How did you first become aware of Punk Rock?

As I said, we'd started to hear about the English scene through the brief stories in the papers. These stories were mainly about the ripped clothes, the gobbing, etc. We still hadn't heard any of the music, because no one would play it on the radio. Finally, we started to hear some stuff late at night on some of the fringe stations. A station called Triad would come on at 10 PM or so, and for years they had the only real progressive rock format in Chicago. With the type of true open-mindedness that is rare, they started to feature punk cuts within their usual list of obscure rock. It was clear that something was going on. But Triad ceased broadcasting not long after that, and the torch was picked up by college radio DJs at WNUR and WZRD. I can still remember where I was when I heard The Saints' "No Time" on WNUR. That was a jolt.

What were some of the first Punk records you got?

The Pistols, Dead Boys, The Saints, Richard Hell, the first two Ramones albums, the Stranglers, the Banshees, Wire, a lot of L.A. music, anything on Dangerhouse; some Toronto music like The Diodes, Teenage Head, The Mods, and singles. Lots of singles. We were all big Stranglers fans. I was still into them until I read Cornwell's autobiography last year. He's gone down a few rungs.

Describe what the Midwest music scene was like at the time before you guys started playing out.

There was no scene in Chicago. There were clubs like Gaspar's, Mothers, and Huey's and we could see bands when they came to Chicago. But aside from a few novelty acts, there was nothing remotely considered punk. The handful of people who hung out at LaMere and O'Banion's weren't into making music. They were into hanging out and being seen. Bands started forming a genuine music scene around 1980. What is strictly called Hardcore developed later, beginning around 1983 or so, and continuing even after we called it quits in 1986.

We took road trips. Milwaukee was a good place to see bands because of the lower drinking age and smaller clubs. If a band was touring the Midwest we'd check listings at Zak's and The Palms and see them in Milwaukee. I also had cousins living in Toronto so we could crash on their floors. Seeing the Dead Boys at the Horseshoe is still the high watermark for gigs. There was a palpable, unstoppable energy that night. All gigs - our own, or any others - have to measure up to that one.

How did you find out about the West Coast Punk stuff? Slash? Flipside? Where did you find those magazines in the Midwest? Did you do a lot of mail order? What record stores out there stocked this stuff?

There were a few record stores in the city - Wax Trax!, and Sounds Good, on the north side. We rooted out the music and the magazines. The people at Wax Trax! were punk fans, so they always had the cool stuff. Sounds Good was more middle of the road, but a few cool people worked there and they stocked a good punk section.

People also talked a lot. Word would get around through a grapevine. People I knew constantly hungered for music and went to great lengths to hear it and inform themselves about new bands. From L.A. there was Slash; from San Francisco, Search and Destroy; New York Rocker from NYC, and a few mags from Toronto.

How did you get to know Tesco Vee?

I think I met him at one of the early shows at Paychecks. Jon Babbin knew him better than I did since he was hooked up with The Fix and knew the Michigan and Ohio bands better.

How did you become aware of the slam dancing/stage diving ritual of Hardcore? Slamming just started occurring at shows. At first, it was cool, a display of energy. later, it became a jock ritual.

How did you get to know Steve Albini?

I met Albini at the Chicago-Main newsstand in Evanston one night. He was talking with these two rockabilly guys and I went up to them. "You guys in a band?" He had some smart-ass comeback. I told him I was with the Effigies. He knew who I was and we settled into a real conversation. He told me he did graphics, among other things, and we talked about our label, Ruthless Records. Ruthless was never a real label, it was a co-op comprising us, Big Black, and Raygun. Every band essentially put out their own records under the Ruthless umbrella, and we all chipped in to get things done. Albini did the artwork. He also steered us to the studio where we recorded For Ever Grounded, our first record. He's a generous guy and has been a big help at times when we needed it. When Earl, Chris, Joe Haggerty, and I got the third line-up together in 1988, he literally gave us the keys to his house and told us we could practice there at any time.

What do you remember about the Detroit band The Allied?

The Allied were fans and asked me to produce an EP. I went into the studio with them and we made a tape. They split up shortly after that and I had no contact with them. The tape sat in my closet for decades until one of the guys asked for it. He's got it now, but I don't know what he intends to do with it.

English Oi! Music played a big part in the early Midwest scene. How did you become aware of these bands? What was your interpretation of these bands? Did you find the idea of English music to be exotic? How much of the English skinhead ideals come into play in the Midwest scene?

I think it's evident from our records that we've always been our own band. Whatever influences we took from other bands are no more than the leanings and shadings we picked up from the music we liked We never tried to be other than ourselves. We tried to be the band we'd want to listen to.

By the time bands were chanting "Punk's Not Dead," it was evident to me that it was. Hardcore was thriving nonetheless, boosted by the easy conformity of political correctness. Like Hardcore Oi! was also a late sub-group of punk. It was uniquely British and there could be no real US Oi! Bands. Still, there were enough cross-cultural issues to bridge certain scenes. The US bands that showed an affinity for Oi! Bands - and vice versa - did so in part out of a loathing for the new crop of politically correct Hardcore bands.

When did the Effigies begin practicing and playing out?

Steve and I were friends from our old neighborhood, and we tried to get our other friends to pick instruments. A few did, but we never formed a real band. Eventually, we got together, and he introduced us to a guy named Norman, who was a regular at O'Banion's. Norman always wore leopard skins and leather. He had a clean, straight girlfriend, had been to England a bunch of times, had a big record collection, and drove a Granada. He also had a big P.A. and a place where we could practice as loud as we wanted.

He became our frontman, and we formed our first band. After a few months, though, I think Steve and I realized it wouldn't work. Norman had a grating whine, and his lyrics were the worst punk clichés ever strung together. The whole thing eventually blew up, with me and Steve walking out, Zamost not far behind.

After that, we tried to make it go as a three-piece, with me singing and playing guitar. One night we went to an after-hours club where we met Earl. Back then you could still tell what kind of music people were into by the clothes they wore. Earl had a jacket with a Ruts badge. He said he was from upstate New York and he played guitar. That was enough to arrange a tryout, and he came to our practice space the next day. It clicked right away. Everybody knew it. We had our band.

We strived for 100% originality. We played no covers. It was tough to put a set together because each of us pulled the sound in a different direction, but we were satisfied with the final product.

What was the initial reaction in the Midwest once you guys started playing out?

It was very hard to get gigs. There was an established rock scene that dominated the clubs, and everyone hated punks. We did our first few gigs at Oz, and opened for Black Flag at the Metro for our third show. We were fans. Black Flag was on tour, and Chuck had appeared on the Tomorrow show two or three nights before the Chicago gig. Tom Snyder, the host - a complete tool - tried to jack with him, but Chuck came off as cool, smart, and not to be toyed with. He had a mohawk, but it would've been obvious to anyone who saw the show that he wasn't posing. This was American punk, the new rock music.

Two days later, we're at the Metro. We're done with our soundcheck and waiting for Black Flag. They toured incessantly and traveled in a white Ford van with a trailer. They were coming from out of town and were late. They pulled up in front of the Metro, and we introduced ourselves as the opening act. One of us said something about the night's line-up and he told us firmly who was playing when and for how long. What an asshole, we thought. By the end of the night, though, everyone was cool. They ended up staying at our place that night. The Anarchy House.

We got gigs out of town and started to develop a fan base. Minneapolis and Detroit were two good Effigies towns, but completely different crowds. We opened for Husker Du on the night the Land Speed Record was recorded.

How did the scene start to grow?

Babbin (our manager and co-owner of Criminal IQ Recs.) and I have known each other since second grade. We had a basement apartment in Evanston that we shared with another buddy of mine. That became the hub of activity for the band. My brother was the bass player for Strike Under and later Raygun. We met the Bjorklund brothers at Club Lucky Number, and we became friends with them. All the bands were really tight, and there was a lot of cooperation.

Jeff Pezzatti had a good PA, and he did sound for a lot of the gigs. I can't remember any friction between the band

What was the initial reaction in the Midwest the first time Black Flag or the Dead Kennedys came to play?

Black Flag came to Chicago way before the DKs. They played Metro in December 1980, when we opened for them. They were pioneers in many ways. There really was no scene yet in Chicago, and the Metro was only about half full, despite Dukowski's Tomorrow Show appearance. Still, it was one of the first big shows with American bands.

By the time the DKs came to Chicago, the scene was already pretty well built up. I believe they played Club C.O.D., which was a very hot venue for about 2 years.

DOA played at the first Oz Club in 1979. It was a hell of a gig, but very few people were there

.What was the reaction when you guys would open up for English bands?

Many of the English bands we opened for were prima donnas. Anti-Nowhere

League was such assholes we untuned all of their guitars on stage before the gig. It wasn't until the UK Subs that we met decent guys. Some of the bands that came after that weren't too bad.

Did you guys ever make it to Detroit to play at the Freezer Theater?

I don't remember playing there. We played Paychecks a number of times,

and almost played St. Andrews Hall at a Touch & Go show, but our gig was the night after some inner-city gangs had shot up the place during a party the night before. Corey decided to cancel the show. We also played Clutch Cargo, which was an old hotel downtown. That was with the great LA band The Flesheaters.

What caused the first wave of disillusion in the Midwest Hardcore Punk?

By the time the term Hardcore came to refer strictly to fast metal, I didn't want anything to do with it. It was clearly becoming a type and a narrow one at that. As is usually the case with that kind of scene, there was one-upmanship and bigoted parochialism. Factionalism, ghettoization. Straight edge, Surf-punk, skate-punk, Rock Against This, Rock For That, all bullshit. We were back in high school.

What were the other clubs in the area that hosted Hardcore shows?

Matt Nelson started doing all-ages matinee shows in the suburbs at a club called McGreevy’s. They were well-run and well-attended. I liked the venue because it was a real club, with a decent stage and a good sound system. There were all-ages shows at a certain club in the city, but we stopped playing there after we got ripped off. Club COD was the perfect venue. Big enough for most touring acts, but still small enough to feel like a club.

What was the first show you guys went to see out of your area and how did it differ from Chicago?

Because we were too young to get into clubs in Chicago, we took road trips to Milwaukee a lot to see bands. There was a really good, tiny club called Zak's up there. I had family in Toronto, so we took some road trips there. The Dead Boys at the Horseshoe is still the high-water mark for live gigs for me. Unbelievable energy that night

.Name off some fanzines that were important to the punk scene developing in America in the 80s.

Slash was the best punk 'zine ever. I regret I didn't buy a copy of every issue. Jack Rabid publishes The Big Takeover. It's not Hardcore, but it does cover punk, intelligently. Its breadth reminds me of how rich and diverse the punk scene used to be.

There were also a lot of tiny 'zines that came out in small towns and were edited by a kid or kids with a love for the music. Some only put out a few issues, but they all did something worthwhile, often with some guts. People forget that in the early days, it was tough to be punk.

The Effigies toured America a few times. What was the reaction to you guys?

We fit really well in the West Coast scene in the early 80s. I loved it there. Despite having to live on as little as $2 a day, I think that the first tour was our best.

How did you feel once you left the Midwest and found out people knew who you were and knew your songs? Were you surprised?

After the first tour to the West Coast, I felt as if we were liked more outside of Chicago than in town. I think I still have the feeling that we were better understood out of town. One of the best things I ever heard was from someone who had been in Berlin before the Wall came down. He said he'd run into some East German punks who had a tape with some of our stuff on it.

What kind of impact do you think the Midwest scene made on the HC scene back then? What kind of impact do you think it made on culture in general?

Very few people can appreciate what it was like to be punk in the Midwest in 1980. Punk is almost mainstream these days. Back then, punks were a scorned minority.

How do you feel about the legacy the Midwest scene has left? Do you even consider it a legacy?

Generally, Midwestern punk bands were independent and lacked pretension. A lot of inspired bands developed their own sounds, and that's the legacy.

So the Effigies still play out. Why did you start doing this again? What's up for the future of the band and yourself?

The Effigies have reformed. We have 3/4 of the original band and we are almost done with the new album. It's as good or better than anything we've done. As I've said elsewhere, we're not a nostalgia act. The new material is good and going down well at gigs. I wouldn't have agreed to play again if it meant simply banking on a 20-year-old setlist. I'm at home in time and place, too. It's 2006; I'm in my 40s; I still have a decent punk album in me.

Thanks for this, Tony. Very inspiring!